All Good Things Come to Pass

Back to the basics.

Life in its simplest forms.

As it was in the beginning...etc. etc.

If you head out into the wilds of the country on a canoe/camping trip and make it as minimalist as possible as far as gear goes, you can’t help but be struck with feelings and thoughts of what it must have been like for the earlier generations of people in this part of the world. I’m talking about the day-to-day conditions of life for all the native people who already lived here and the European explorers who later came to North America , who all traveled and lived much the same way out in the wilderness areas. For them it was a real-life, ongoing ‘camping trip’; living in harmony with the earth with little more than their own talents and strength of will to help them exist and survive.

The glaring difference between them and me is that they couldn’t simply pack up their few things and find their way back to a modern, luxurious city or town somewhere relatively close by, closing the door on the stark realities and challenges of raw nature, as I can.

I’m sure my experiences and observations on my little trips aren’t unique at all and probably not uncommon among the people who like to do this sort of thing as I do.

However, it is one thing to hear about something and quite

another to experience it for yourself.

Experiencing something for yourself changes you sometimes, in ways that simply hearing or reading about it could never do.

I’ve taken long river trips on which I’ve taken no food or water with me. I would rely on catching fish, ducks or small animals for food. I’d consume water from the rivers. It all seems exciting and even romantic at first but sometimes you go 3 or 4 days without catching anything and then it becomes a bit more real. The game changes from being an experiment, to becoming a bit more desperate. You fish more carefully. You pick your spots more smartly and refine your techniques. You begin to experiment with sounder methods of trapping a bird or muskrat. You notice plants and berries that can be eaten when it all just looked like miscellaneous foliage before.

On some of the rivers in western Canada, it can be days and days before you’d ever pass even close to a town or village and even then it might mean a 1 to 6 hour walk through pretty thick bush to get to some of them.

But on all these trips I’ve always believed that I’ve never been in any real danger. Barring some tragic accident that might leave me stranded in some way, I was never ever really worried about things. I knew, if worse comes to worst, I could always just sit in my canoe, day and night if I needed to, float along with the current and I’d eventually arrive at some town on the banks of the river long before I’d ever starve to death. Few rivers in Canada flow from source to outlet without passing at least a couple of towns or cities on the way.

All in all, even though it isn’t exactly the same circumstances and conditions experienced by the early explorers, fur traders and natives of centuries ago, you still do get a real taste of just how alone you are on this planet; that’s still there, probably as it’s always been.

Or of how huge everything else is when compared to you; that’s still there, probably as it’s always been.

That your blood is really no more significant than the blood of the coyotes you hear crying at night in the bush behind you or the blood of the goose or fish you captured for dinner. We’re just one more predator or meal in the long chain of nature.

And you especially notice that to live, you really don’t need a lot of stuff and it makes you aware of how incredibly bloated and excessive our society has become as it becomes less and less aware of that fact. Constantly replacing what it already has with the next 'newer', 'better' thing.

But this isn’t exactly what I wanted to write about in this text.

My little wilderness adventures, though many and varied, aren’t likely to be too interesting to anyone else except me. It’s perhaps better to keep them in my memories or as odd stories for around a campfire with friends, sometime.

The reason I started with these few paragraphs was only to give you a sense of where my mindset has drifted to at times and why I was suddenly curious, one day, to dabble in a little project or experiment, about which I want to tell you. I was impressed with the ingenuity of man in those days to provide for himself using the things around him and his own intelligence; a skill that seems to have diminished these days, somewhat.

It isn’t world changing, or anything like that, but the things I discovered from a simple object really surprised me. I suspect they are just a few more of those little things that fade away and quietly disappear altogether from the general knowledge, history and consciousness of humanity, as time rolls on and progress crushes all in its path.

As you could probably surmise about me, I like writing.

Always have and ... well ... always have.

Words seem nearly magic to me.

Writing provides an almost therapeutic outlet for the thoughts of the person putting them down on paper. It’s fascinating that these words of someone perhaps long since dead and gone from our planet can speak to future generations, across time itself! This idea of creating a direct bridge of communication between two people, years and years apart from each other, is amazing to me. Notwithstanding talent or purpose, writing today is a relatively simple thing to do and can be done in many different ways. Postal services, text messaging, word processors, sky writing, newspapers, fancy gel pens, language translators, email, even Etch-a-Sketch if you’re thumb and forefinger gifted, ... the advances in the process of getting your thoughts out of your head into a format for others to read, are most impressive, aren’t they?

It was during one of my canoe trips, while I found myself in a ‘historic’ frame of mind out there alone in the bush, that I began thinking about the act of writing as it probably was back in the ‘old days’.

It was basic then.

Pretty much only paper and pen. No flashy, colorful, popping screens or clever sound bytes to mask that the messenger really had nothing relevant to say at all. No, instead, if you were solid, your words lasted, if you weren’t, they didn’t. ( Wouldn’t that be refreshing to see again? Less quantity and more quality? )

That evening, I imagined being alive in the 17th or 18th century and wishing to write down my ideas.

I know few people could read in those days, let alone write, but what if I were one of those who could?

As I sat there by the fire, I looked around my camp. I wondered how I would get all the materials I would need to write to my yet-unborn self 200 years in the future, if this were indeed the year 1800 in the middle of the not-yet established western Canadian wilds (or 'Canadien' would probably be more appropriate in this case).

Surrounded only by rocks, trees and water I realized there’s so much we take for granted in the modern world, isn’t there?

I would need paper.

Where would I get that?

I would need ink.

Where would I get that?

I’d need a pen.

Paper. Before the discovery of mass-producing paper from wood pulp, it was usually made from old cloth rags and wasn’t cheap compared to the other consumer products of the times. Even so, most people of the 1500s and on didn’t make their own paper. Lack of skill and experience generally produced low quality, substandard results so naturally, over time, specialty ‘trades’ of people appeared. Paper makers. If you were an artist, businessperson, or writer, you could seek out a merchant in the cultures of Europe and Asia who could supply you with good sheets of paper. It wasn’t as abundant as we know it to be in our modern age, but it wasn’t impossible to find and buy. Not surprisingly, a lot of monks and priests were very accomplished paper makers obviously due to the needs of their professions to reproduce and maintain their texts and doctrines.

Ink, too, was generally made by trade’s people specifically in business to do so. It was made from a variety of ingredients that varied depending on ink color and country region but was generally bought as opposed to made, by the common folk. At times blood has even been known to have been used as an ink in the absence of having the actual stuff ( or while selling your soul to the Devil *grin* ). You could usually purchase a little inkwell of ink from the same suppliers who could sell you the paper.

Pens were different.

You didn’t purchase a pen and usually nobody sold them.

You created your own.

Part of knowing how to write was to know how to create your own pen to write with.

It would indeed seem odd to us today to go into an office supply store and be able to find everything we can today but absolutely no pens or pencils. Suppose they simply were not produced or sold. Suppose we were expected to make our own. That’s how it was for many millennia almost to the mid 1800s.

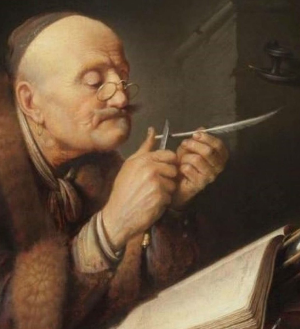

Back in time, many things were used as ‘pens’ in various regions of the world. For example, the Chinese used small brushes. Some Arabic groups liked to use porous, sharp wooden sticks that they dipped in ink. But what became quite common and popular, especially in the European cultures, and later throughout the world as exploration began, was the quill pen or feather pen.

A large feather or quill from a goose or large pheasant would be found (or pulled right off the unsuspecting bird). Using a very sharp blade or edge, the person would slice off the tip of the quill at a sharp angle and then trim this until it was nearly a point with a tiny blunt end. They could then dip the end of this cut quill in a small inkwell and use it as a writing instrument.

In fact, over the centuries, a small, sharp knife designed specifically for this purpose was developed. People wishing to write would acquire one of these knives. They’d use it to fashion the sharp, precise cuts on their quills and it soon became known as a ‘penknife’. You may notice that small ‘jackknives’, even to this day, are sometimes called penknives even though the original meaning of the name is probably lost on most people.

In schoolhouses, one of the first things often taught to the older children, ready to move past chalk and blackboard tablets, was how to create a proper quill pen from a large feather with their new, little penknives. Most would bring their own feathers to school from the yards of their own homes. ( With the hysteria over weapons in our schools these days, it is amusing to think that nearly every ancestor student would have to surrender his or her little penknife at the entrance of the school nowadays ).

Anyway, as I sat by my campfire that evening, I walked through the scenario in my mind of creating the materials I would need to write down my thoughts and quickly realized it would be a more ambitious project, considering where I was, than I was willing to undertake at that time. The purpose of my trip, after all, was to enjoy nature, discover things as they came along and reflect on life, etc. I wasn’t there to surmount spontaneously created, difficult challenges from my daydreams. So I thought about the dilemmas and challenges of my forebears and their writing and like most people, alone with their thoughts, I soon pushed it all into a corner of my mind, forgot about it and moved on to other things in my day.

It wasn’t until months and months later that these thoughts resurfaced.

I was in a park in the city. I had bought a loaf of bread and had stopped there to feed it to a dozen Canada geese that had taken up summer residence on the big pond not far from my place. As they fought over the morsels of bread, hissing and pecking at each other, I noticed several very large feathers on the ground around them. Canada geese are quite large birds. I noticed their biggest feathers are what I would judge to be very good prospects to be used as quill pens. As I sat there, feeding them, I remembered my campfire musings about writing back in the olden days. I grabbed a few of the biggest feathers and tucked them into my jacket.

You must understand that I had absolutely no experience using a quill pen. I hadn’t ever seen one except in movies and even then, not up close. I certainly had not ever used one. I had used, however, those metal tip things you insert in a handle and then dip in ink to write with. They were probably the first invention of a manufactured pen, after the quill. One thing I’ve never liked about them is that, no matter what type of ink or paper I used or however lightly I applied pressure, they seemed to ‘scratch’ the paper and caused the ink to ‘bleed’ along the edges of the letters I wrote. If you looked closely, the letters appeared to be fuzzy, not crisp. They also tend to drop a blob of ink when you first write after dipping them for a refill of ink, especially if you’re not careful to first remove most of it before you do so. They go dry quickly; you must dip often.

I’ve also owned a few fountain pens in my day. They all had tiny rounded ends on their tips. You couldn’t scratch the paper with them and this fuzzy letter syndrome wasn’t an issue. They are certainly enjoyable to use but it can get messy sometimes when you have to refill them if you don’t follow strict procedure in carrying that out. And the leaking pen in the white shirt pocket was a common thing back in the early part of the 20th century. My pens eventually couldn’t ‘suck’ up ink properly anymore and that was the reason I had to let them go.

But, back to my story...

My thoughts had drifted back to the writers of long ago.

I finished feeding the geese and returned home with the few big goose feathers I had taken.

I was determined to create a quill pen just like people did back in the

1700s.

I had no expectations, only curiousity about the process.

I got my extremely sharp jackknife out.

I had a small inkwell of blue ink already.

I had plenty of white paper around.

I laid the feathers out on my desk in my office and looked at them.

The shafts, at the base, were ¼ to almost ⅜ of an inch wide; very comfortable to hold in your hand as a pen.

The feather has a natural, slow, long curve to it. The feathery part is wider on the inside of this curve and short and cropped on the outside. When you hold it in your hand, it feels more natural with the wider feathery side downwards, resting on the back of your hand.

Using this as my only judgment as to which side of the tip to make my angled slice on so that my finished quill would rest in my writing hand this way, I took my knife and proceeded to cut the tip off at a steep angle.

Understand that my knives are always very sharp. Like razors almost. I take pride in keeping them that way.

But I discovered this quill was tough.

I immediately realized that it wasn’t very easy to cut. Kind of like cutting through fingernail material or something similar.

My first cut tore more of the quill than slice it. The result was shabby and ragged. No good.

I needed to try again.

I moved a few millimeters up the shaft and took a second try but this time made it a quick, decisive motion with a strong grip.

I got a clean cut with a tip that looked like a sharp, hollow arrow.

I looked inside the shaft of the quill and noticed something. Along the top of the inside of the shaft tube, there is a strange looking little ‘pocket’ of shaft material hanging down from the ceiling. It’s a very thin, delicate membrane that dips to a ‘V’ shape in the middle and is attached on each side to the left and right inside edges of the shaft tube. Imagine a long tarp or awning loosely suspended inside a long pipe. It kind of looks like that. It’s made of the same material as the shaft itself but is much thinner. It’s not consistent along the entire shaft and at times there are small breaks in it. I found that it is preferred to make your pen tip slice at a point where this membrane is complete and fully attached. I will explain the reason why shortly. This isn’t difficult to achieve. If your first cut doesn’t give you this, your second one most probably will. The small breaks in its continuity aren't common.

So now, I had my clean slice. I then took my knife and carefully carved each side of the ‘V’ to narrow it and create a slight inward curve in each side. (I was trying to mimic the shape of the tips of the manufactured metal inkwell pen tips I had). When my carving had worked its way down to producing a point about less than a millimeter wide for about 3 or 4 millimeters long I placed the tip, bottom side up, on my desk and using my knife like a small hatchet, chopped off the very tip to create a clean blunt end, almost a millimeter wide. I also made sure to cut it at a slight slope to the left so it would feel more natural as I wrote with my right hand. (The pen sits at a slight angle in a person’s hand so the tip works better if its blunt end is cut on a slight slope to accommodate this position).

My pen cutting and testing took a few trials during this learning curve. There are things that I initially tried, based on trying to imitate manufactured metal pen tips, which proved to not work very well at all for quill pens, especially compared to what I finally discovered through trial and error in my later designs. I could mention these setbacks if you wished but instead let me describe the pen when I finally came to a design which worked well for me.

Most ink dipping pens have a slit cut up the center line of their tips to a point above the ‘V’ to where there’s usually a tiny hole. This hole holds ink in a mini, suspended droplet that then bleeds down to the tip as you write. This system is designed to act like a reservoir for the ink. After it all soon drains away, you must dip once again to continue writing. I tried this design feature on my pens as well but it didn’t work very well for me so I decided to abandon it.

My final quill pen didn’t have this slit. Instead, I would dip my pen and a tiny drop of ink would collect in that membrane I mentioned earlier; the little V-shaped pocket of material on the underside/inside of my pen shaft, that acted as a natural little reservoir for ink. The ink would then flow down the outside edge of each side of the pen’s ‘V-tip’ towards the end, out onto the paper.

Try to picture this:

There was no slit in my pen.

The ink moved from the quill membrane pocket reservoir, wicking along the outer edges of the V cut, down to the tiny pen tip, onto the paper.

Another advantage of this functionality is that it allows for the creation of very tiny pen tips, right up to virtually pointed ends because you aren’t bisecting them with a cut slit that compromises their structure or strength. (I find this very handy while drawing, when the need arises for very narrow, thin lines).

I discovered the material of the feather shaft seems to allow ink to flow smoothly on its cut or sliced surfaces but ink tends to ball up on natural, uncut surfaces. This is very advantageous in creating a quill pen. The inner membrane is a natural undisturbed surface area so the ink ‘balls’ up in there as a tiny droplet. But the edges of this ink reservoir membrane also coincidentally mate exactly with the top of the edge of pen ‘V’ tip once you cut into both, so the flow/transfer of ink is natural and smooth from the droplet right to the very end of the pen.

This was very intriguing to observe.

It is almost as if Nature created the feather (at least the

Canada goose feather) exactly for making into a pen device.

It's incredible to see material with properties for allowing ink to flow or to not flow, in exactly the right locations and placement to allow for the creation of a writing instrument.

But it didn’t stop there!

I’ve used a lot of ink dipping pens in my time. On upstrokes of letters, you must be careful to regulate your pressure because sometimes you’ll inadvertently be applying too much and the tiny tip will ‘stab’ or 'grab' the paper and cause the sharp tip to dig in or skip. The result is a jittery stroke that sprinkles ink droplets around your poorly formed letter character. Messing your page.

My quill pen didn’t do this. The shaft material, when carved properly to a narrow tip, simply bends with your hand pressure and adjusts its angle on the paper accordingly. The only drawback to excessive pressure is that ink delivery changes and sometimes you get slightly lighter or darker colored characters than the bulk of them. But there is no skipping or droplet splatters. No mess at all. In fact, the flexibility of the feather shaft material was a very unexpected and pleasant discovery to me. When the resistance against the paper is constantly adjusted by the flexibility of the material against your varying hand and finger pressure, the writing becomes effortless and requires no concentration on technique. Especially considering that every letter isn’t ever applied with the same pressure as the other and your ‘passion’ while writing may change according to content and this in turn usually causes pressure changes as well.

I soon discovered that by carving different styles of tips I could make one custom suited to my exact style of writing pressure. If you like to press hard and write fast, you make your tips leaner and more flexible. If you tend to write lightly, a wider one does you better.

And writing, as opposed to printing words,

works better with a sharper tip than a blunter one.

A pen designed exactly for the user. What a concept.

Not once did I ever experience the fuzzy letter syndrome of the manufactured metal pen tips I had used in the past and mentioned earlier, up above. The quill tip applied its ink to the paper forcefully enough to produce consistent crisp, dark letters but never so much as to tear the microscopic fabric of the paper surface to cause the ink to ‘bleed’ around the lines of the letters like the other metal tips did from time to time.

Finally, one thing really surprised me. And it turned out to be the knock-out selling feature of the pen for me.

Through the years I’ve always known that ink dipping and writing is

nostalgic and that alone is somewhat pleasing but the constant re-dipping of the pen to reload with ink, to me, is

sometimes bothersome and intrusive. Especially when you’re writing away, in the

middle of a thought, and suddenly you run dry, have to stop, and reload the

tip. At times it feels like a mechanical process thrust into the middle of a creative process. A clash.

But here I was, writing away with my new little quill pen.

And writing. And writing. And writing.

I wrote a third of a sheet of paper and only then was I starting to run dry. I thought this an anomaly so I reloaded and continued writing. Once again, I wrote word after word until I had another third of the page filled. Once again, only then did I start to run dry and need to reload.

I was amazed at this. I had never used any tip capable of this, in the past, ever!

Usually loading your ink dip pen with a big drop of ink, so you can write for a longer time, means you risk the chance of it falling to the paper in a huge messy blob of blue or black as you begin writing or are 2 words into it. But this didn’t happen with my quill. I’d dip it heavily. I’d scrape the excess off the tip on the edge of the inkwell and then I’d simply write as normal, not worry about my initial few letters beginning too forceful or the ink being too dark or heavy. The ink flowed evenly from start to finish with hardly any difference in intensity until it finally ran out and not once did I ever experience the dreadful blob-of-ink dropping from the pen onto the page.

Best of all, refilling the tip of your pen feels much more natural after a paragraph of thoughts rather than a sentence and a half of them. It was very natural and pleasant to write with the quill in this way; having to refill it only just as my natural tendencies and thoughts paused as well. Think about this for a second. This is a very nice feature to writers of any kind. The mechanics of the pen become almost invisible to you as you pause, absent-mindedly dip it, all the while formulating your thoughts for your next block of text.

Also, from an artistic point of view, writing with the big quill looks and feels kind of cool too. You feel like you’re in some smoky little attic somewhere in Europe or New England, a couple or three hundred years ago, penning out a novel or letter or last-will-and-testament or something.

It all feels a little surreal at first. Like you’re cheating society when you can make something like that, for free, with a sharp knife and a discarded feather, and use it like something you’d normally have to pay good cash money for.

But, you know, the sad thing is that hardly anyone actually writes by hand anymore.

Computers have created instant life.

Life on crack.

Instant info, instant contact, instant purchase, instant sell, instant messages, instant friends, instant enemies.

The ‘long-hand letter’, written with some time to reflect on the words going down, written with the character of the person’s handwriting, reflecting their emotions and feelings at the time, placed in an envelope, sent on its way through the mail; that's soon to be an extinct creature. People today don’t even seem to have time to write the English language in full or properly let alone learn it and use it in this traditional way anymore. Messages today are mostly electronic and full of quick, short abbreviations for expressions and phrases. It seems to be easier for people to quote a popular saying to reflect a general feeling or thought than to come up with a sentence that says a bit more, a bit clearer or in a more clever way, from their original thoughts.

But it all doesn’t really matter I suppose.

Everything is destined to evolve or fade away or, in the case of writing, both.

I just never thought the day would come for me when I’d see the gap so clearly between what I cherish about society and what it is slowly becoming; a way I don’t cherish as much.

My little quill pen experience only showed me that this has

always been going on and I shouldn’t feel bad to notice it happening to me.

After all, I too would have been guilty of not knowing about something I didn't know had been, simply because I didn't take the time to investigate or dream a little.

So I just want to say, to all you old guys and gals back there in 'time' and in the history books, long since dead, gone and forgotten, who used quill pens as your bread-and-butter during your lives:

I’ve discovered it and it is truly a surprisingly superior

instrument, considering what it is, to anything invented since.

It works in

harmony with the natural rhythm of how a person writes and thinks.

It can be tailored so exactly to a person's writing style that it becomes an extension of your thoughts and not just a tool at the end of them.

Because

of this, it probably helps in the production of the works.

It helps you pause, think and breathe.

Maybe that a lot of our most revered literary, philosophical, and scientific works all seem to come from times when they were probably penned with nothing but quill pens isn’t too coincidental after all?

And as far as the esthetics of it, it beats everything else, hands down.

I don’t have much else to say about it…

It’s just sad to me to see things of simple beauty and perfection, no matter what

form, go away…